According to a University of Iowa study published by the American Chemical Society, between 51,000 and 79,000 Iowans are at risk for lead exposure in drinking water that exceeds the threshold set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Amina Grant, a Ph.D. student studying civil and environmental engineering, was lead author on the study which examined now many Iowans may be consuming drinking water that has more lead than is allowed by the EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule (LCR).

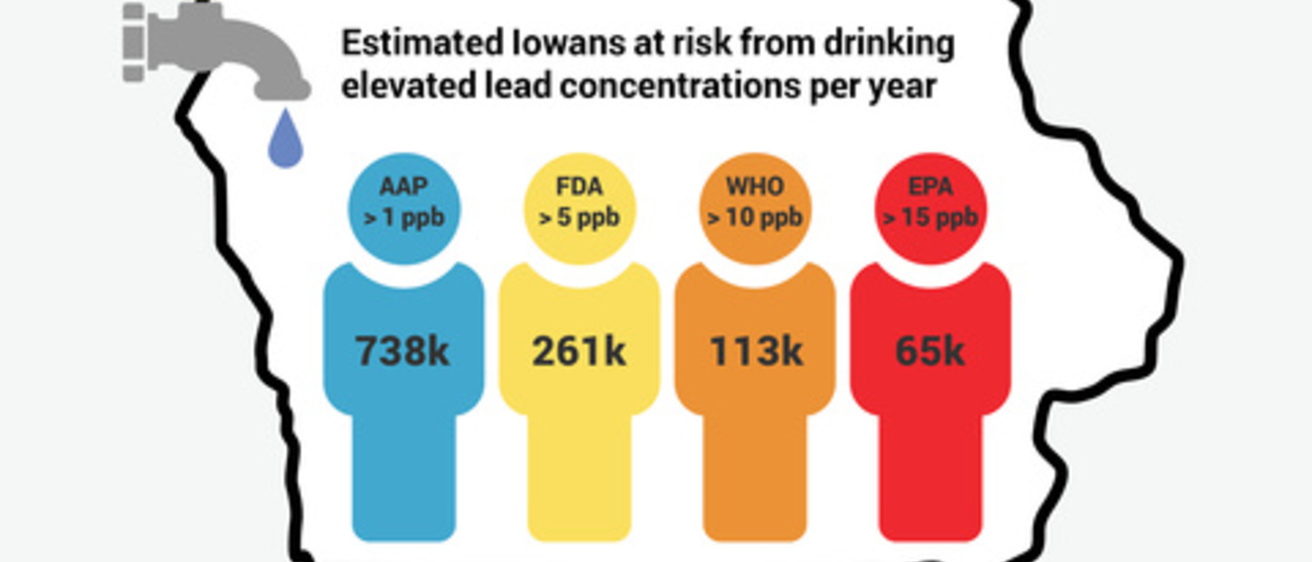

“The EPA established the LCR in 1991, but that is only one way in which lead levels in drinking water are assessed,” said Grant. “There are much lower thresholds set by the World Health Organization, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and the American Academy of Pediatrics. We wanted to see how many Iowans may be exposed to lead at these levels.”

As part of a class project, Grant developed a computer program that would gather data on drinking water lead levels from a publicly available database. The database contains entries from communities of various sizes from across the state of Iowa. Grant notes that 90% of Iowans receive public water, while the remaining 10% are on private wells.

Grant’s advisor, Michelle Scherer, the Donald E. Bently Professor of Engineering in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and a co-author on the study, says it is somewhat surprising that these kind of estimates haven't been done before. "The long-term benefit of Amina's work is that it lays out a simple, but rigorous way to get a handle on the potential extent of lead in public drinking water,” said Scherer who added that “it would be very useful to use this kind of approach in other states to map out the extent nationwide.” Scherer cautions, however, that Amina's worked looked only at public water. "No regulations are currently in place for private well water and drinking water in school and we need to do more to assess the extent of lead in these drinking water sources as well."

“While we have been lucky to not have major lead-in-water crises in Iowa, the genesis of our work was our observation that several small water utilities in Iowa had exceeded the 15 ppb LCR action level. Amina’s study highlights that a small percentage of homes are sampled for lead. We encourage anyone with an older home or young kids to get their water tested for lead,” adds Drew Latta, a research scientist in IIHR-Hydroscience and Engineering and a co-author of the study.

The lead levels established by the EPA represent a utility-centric approach, and Grant and her team believe that their findings make the case for developing a more consumer-centric approach to lead in drinking water policies. For Grant, the EPA’s trigger for actions, lead levels that exceed 15 parts per billion, may not be the best standard to protect Iowans.

“Unlike other metals, lead offers no health value and can have detrimental effects such as increasing blood pressure and damaging brain development in children,” said Grant. “If we assessed risk at lower levels of lead in drinking water, we could better protect Iowans and mitigate the negative impacts on public health.”

The full study, “Estimating Consumers at Risk from Drinking Elevated Lead Concentrations: An Iowa Case Study,” can be found here: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00753#.