By Richard C. Lewis

University of Iowa Strategic Communications

For nearly a decade, Goodell, Iowa, has struggled to solve its wastewater treatment issues.

Like many small towns across the state, Goodell has been ordered to either upgrade or replace its wastewater treatment systems to comply with water pollution regulations. Whether from federal or state officials, the rules have been difficult for many communities to comply with.

The fixes don't come cheap, though. Goodell, a Hancock County community with a population of 179, is considering installing a wastewater treatment system that would raise residents’ rates by as much as $95 per month.

“We know what needs to be done; we just want it to be a little bit cheaper,” says Goodell’s mayor, Ryan Halfpop.

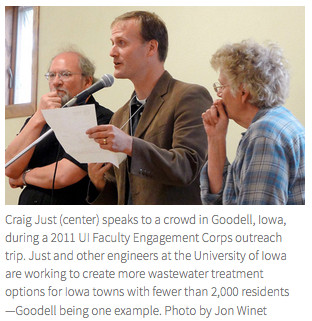

That's why engineers at the University of Iowa are working to give Iowa towns with fewer than 2,000 residents more wastewater treatment options. The plan, says Craig Just, UI civil and environmental engineer and the project’s lead, is to test commercially ready wastewater treatment technologies and gather the information required by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources to certify that a system would work in the state. The more wastewater treatment methods tested and approved, the more choices available for small towns—at presumably lower cost.

“It’s like the chicken and the egg,” Just says. “(The DNR) won’t say a technology can be used until it has the data. But small towns in Iowa can’t afford to try out new technologies and get the data the DNR needs to approve the system. We could provide that service.”

The Iowa Small Community Wastewater Research Program, Just says, could impact more than 800 communities in Iowa’s 99 counties over the next 25 years.

He envisions testing up to three commercial wastewater treatment technologies at a time on a plot adjacent to Iowa City’s Wastewater Treatment Plant on the south side of town. Some wastewater would be diverted from the Iowa City plant to the test systems, and the treated water would be returned to the Iowa City plant for additional cleaning, if needed.

“The nice thing about doing it at the Iowa City plant is treated water from the testing sites can be routed to the city plant,” Just says, “so if a test system doesn’t work, the water still goes to the wastewater plant and gets cleaned.”

Iowa City administrators support the proposal, Just says, and Iowa City's City Council would need to review and approve the plan.

The site also could be used to test recently built small-community wastewater systems to learn how to optimize performance and how to appropriately size them.

“They're in a special kind of pinch point,” Just says. “They can’t afford to do modern wastewater treatment in some ways. How do you bridge that gap?”

The next hurdle is obtaining the money to start the research. Just has estimated the program would cost $2.75 million to launch and need $1.8 million annually to install and test treatment technologies, report results, and train operators. That said, he estimates the initiative would save Iowa small towns more than $100 million in wastewater upgrade costs.

“That’s money for those communities to grow and look toward the future,” says Just, who’s from Eagle Grove, a north-central Iowa town with about 3,600 residents.

Communities are required by federal and state agencies to remove or strictly limit pollutants, including fecal coliform bacteria, nitrogen, ammonia, and phosphorus. More recently, Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy began calling for greater limits on nitrogen and phosphorus release from municipal wastewater facilities when they renewed their discharge permits.

Small towns across Iowa have found it challenging to keep pace with the wastewater limits, especially if they’re losing residents and businesses. The result: Fewer people shoulder the wastewater treatment upgrades or overhauls needed to comply with water pollution regulations.

“They’re in a special kind of pinch point,” Just says. “They can’t afford to do modern wastewater treatment in some ways. How do you bridge that gap?”

One solution could be to have companies test their own technologies. But Just says firms aren’t willing to front two years of costs (as required for permitting) and to test for pollutants, such as nitrate, that aren’t regulated in many other states. Perhaps as proof of his argument, he says only three alternative wastewater treatment technologies have been approved for Iowa.

“When the market can’t—or won’t—do the testing itself, or it doesn’t make sense for them to do it, then you’re left with a stifled market,” says Just, who's also an assistant faculty research engineer at IIHR–Hydroscience and Engineering, part of the UI College of Engineering. “This is a perfect opportunity for a research university like the UI to come in and do it.”

The town of Wilton certainly would have welcomed more choices. The eastern Iowa community of roughly 2,800 was ordered two years ago to upgrade its operations to remove iron, says Chris Ball, Wilton’s city administrator.

While Wilton now has a plan in place, Ball says, “If we could go back five years and Craig’s information (on other wastewater treatment technologies) was available, we might spend $2 million to $3 million instead of $5 million to $6 million,” including $800,000 in research costs.