By Jean Florman

Risk-takers. Dreamers. Extroverts. Words not often used to describe engineers -- at least not in popular media.

But for decades, the University of IowaCollege of Engineering has turned out engineers who have blazed their own trails as entrepreneurs—the very definitions of

risk-taking dreamers whose paths to success have been smoothed by their “people-person” skills, and who truly embrace the college’s “engineer…and something more” concept.

After 17 years in engineering sales for two prominent sanitary engineering process equipment manufacturing firms, Philip Parsons (

plunge.

“As a kid, I was always watching neighborhood construction projects and asking the workers to let me ‘borrow’ scrap and leftover lumber to enable me to build my projects, much to the chagrin of my parents,” Parsons says.

“In high school I enjoyed classes in math, science, and architecture,” he added. “During summers and holidays in college, I was working as a surveyor and then as a designer for a consulting firm in my hometown of Detroit. This gave me valuable experience in various civil engineering disciplines, and gave me insight about the nature of becoming an entrepreneur.”

Inspired by his engineer father and encouraged by Professor of Civil Engineering Wayne Paulson, Parsons decided to enter the new UI program in environmental engineering just as the federal Water Quality Act of 1965 created the Environmental Protection Agency and began providing substantial federal funds for environmental projects.

“I knew then that I wanted to participate in this engineering profession from the ground up,” Parsons says. He adds that the spirit of trying to master something new is what entrepreneurship is all about.

But before he launched his own business, Parsons spent 16 years learning the ropes as an application engineer, research and design engineer, and technical equipment sales engineer for two of the largest suppliers of water and wastewater equipment in the Midwest.

In 1982, he decided to strike out on his own.

“I was very happy in each of my previous work experiences,” he says, “but we had furnished a lot of process equipment for municipalities and industries which made a lot of money for the companies where I worked. So I decided it was time to start my own firm to follow the entrepreneurial spirit that was within me. I wanted to convert some of my energy and prior successes in business to make money for myself in proportion to my effort. And I would like to think I was ambitious and liked to do things my own way without needing approval of management above me.

“Starting my own company was a way I could implement my ideas unfiltered by decision making layers you typically find in corporations,” he says.

Parsons adds that being confident in your decisions doesn’t mean you don’t want to listen to trusted, experienced, intelligent people around you. In fact, successful entrepreneurs seek out those individuals, which is precisely what he did when he “cherry-picked” nine of the best people from his former firm and convinced them to join him in his new venture, Parsons Engineered Products, Inc. most recently headquartered in St. Louis Park, MN.

“We tried on several different names for the new company for size,” Parsons says, “but the abbreviation, PEP, really said something about the drive and spirit of the company. Other names we considered—Parsons Environmental Engineering, or Parsons Institutional Sewerage Systems, or Parsons Outdoor Occupational Product. Well, really, those wouldn’t have worked so well.”

By the time he retired in Fall 2014 and sold the entire company to one of his business associates, Parsons employed some of the finest environmental engineers in the region.

The company’s work continues to be recognized by its peers across the upper Midwest. Parsons says he enjoyed his work nearly every day of his career. More than 70 of his friends and colleagues traveled to Minneapolis from around the U.S. for his retirement party to recognize the achievements of his 48-year career in environmental engineering.

Since retirement, travel with his wife and family has been a great way to enjoy life, although he continues to be interested in environmental engineering management and projects for which he is committed to consult with the new owner for at least several more years.

“I’ve always been fortunate to have good people guide me,” he says, “and I hope to return the favor to others who can benefit from my many years of experience. I enjoy sharing ideas with others, including the new business owner, hoping its advice they can use.”

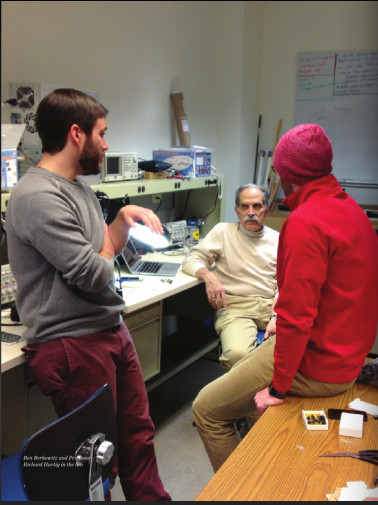

University of Iowa doctoral student Ben Berkowitz (BSE 2010, MS 2012) didn’t step into the entrepreneurial world from a successful career in the corporate

world—he’s never been in the corporate world. Nevertheless, as a doctoral student in biomedical engineering, Berkowitz is already a deeply committed entrepreneur and the development director of Voxello, a start-up company headquartered in the University of Iowa Research Park. Voxello designs, develops, and manufactures innovative technology to augment the communication abilities of hospital patients who are severely incapacitated.

Voxello came to be from students in the Iowa Medical Innovation Group (IMIG). The students began collaborating to address the question of how to enhance patient care for people who could not verbalize their needs or condition. For years, Hurtig—who now serves as the Chief Science Officer for the company—had worked with the UI Hospital and Clinics Hospital Assistive Devices Lab to design devices for the particular communication needs of individual patients.

Now the company’s goal is to create technology that is adaptable to a range of patient communication modes, whether blinking, lip pressure, or small movements.

“We’ve developed a device called the noddle™,” Voxello Product Development Director Berkowitz says. “Patients can use it to call a nurse, turn on lights, and respond to questions. In every hospital there are patients who have the mental ability to communicate, but can’t because of physical impairment. This device will open a whole new way for these people to control their environment and express themselves to care providers and family members.”

About the size of a checkbook, the noddle™ can interface with iPads™ and dedicated speech generating devices. It distinguishes the difference, say, between involuntary blinking and consciously generated eye movements for communication. It can be used by virtually any adaptive switch and attaches to a hospital or home surface with a few zip ties or clamps. Voxello CEO Rives Bird estimates that the use of the patented device could avoid 350,000 adverse patient events per year—events such as falling out of bed when reaching for a nurse call switch— including 1,000 lives per month. That safety improvement also translates to $3 billion in savings to patients, hospitals, and insurance companies.

“This technology takes into account all the factors that patients experience in a hospital and adjusts to their needs,” Berkowitz says. “A patient with a single capability can control multiple devices to call a nurse, communicate with visitors, or even administer their own pain control medicine.”

In January, the startup company signed an exclusive global licensing agreement with the UI Research Foundation and finished manufacturing the clinical prototype which will be used in hospital trials. The team has secured funding from a number of sources, including $350,000 in nondilutive funding from the UI Research Foundation and State of Iowa Economic Development Authority, and $250,000 in private investment.

“This is such a great experience,” says Berkowitz who passed his comprehensive exams while working full-time with the company. In December he also won the Grand Prize in the John Pappajohn Entrepreneurial Center’s Venture School Business Model Competition which features local entrepreneurs who describe how they have created successful business models and secured customers.

“There aren’t many grad students who have the opportunity to help start a tech company before they’ve graduated,” Berkowitz says. “In a large corporation, I would just focus on one thing. Now I develop devices, yes, but I also am involved in fundraising, communication, managing teams of interns, and manufacturing. It’s a lot of work and a lot of fun.

“The University of Iowa has been a wonderful launchpad for me,” he adds, “and I am so fortunate to be able to work with these other researchers. The rate at which I’m learning and the variety of experiences I’m exposed to every day would be pretty hard to beat.”

While the entrepreneurial paths chosen by Ben Berkowitz and Phil Parsons remained clearly aligned with engineering, Kendra Wyatt (1997 BSE) traveled an entrepreneurial path that has taken her far from her industrial engineering roots. Or so it seems.

Wyatt is the co-founder of New Birth Company, an Overland Park, KS startup that offers natural childbirth experiences for women and their families.

“I’ve always wanted to work in healthcare, not manufacturing,” Wyatt says, “and to focus on policy’s impact on how business works. Industrial engineers study decision making and, ultimately, the process of how policies are crafted and implemented. And the American healthcare system is one giant decision-making process that needs help.”

At Iowa, Wyatt began her studies in biomedical engineering, but soon discovered that in industrial engineering, she would be able to study anthropology, economics,

and psychology.

“I loved that in IE, I could step back from what was happening in a particular context and ask, ‘What is it that this particular culture values?’”

She also took a Master’s level course in healthcare administration, and during a co-op at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, she worked with industrial engineers in charge of quality and performance improvement.

Following graduation, she began a steep trajectory of success as a “serial intrapreneur”—an employee in a large corporation who is responsible for taking risks to innovate and create a profitable end product—at Cerner Corporation, a multi-hundred-million-dollar company whose 15,000 employees provide technology solutions for healthcare systems worldwide.

Shortly after starting at Cerner, Wyatt was appointed to be the assistant to the CEO, a unique opportunity that allowed her to observe how to lead a fast-growing company from Neal Patterson, “one of the smartest and more vibrant entrepreneurs on the planet.” And although she had long wanted to launch her own company, it wasn’t until a ten-day sabbatical in Rwanda with renowned anthropologist and physician Paul Farmer that Wyatt was “struck by possibilities.”

“I came back on fire,” she says, “and when I met the nursemidwife who delivered my second child, I decided I really could make a difference in the world by helping to provide a dramatically different childbirth experience for other women.”

Wyatt decided to leave Cerner, and four years ago, she and the nurse-midwife, Catharine Gordon, teamed up to create New Birth Company, whose mission is to establish high performing birth centers that consistently provide safe, natural childbirth care. Wyatt’s role is to tackle “all the complexities of budgeting, insurance, and regulatory requirements so the midwives can focus on catching the babies.” Two New Birth centers provide birthing and maternal and newborn

care services to low-income women in the Kansas City area.

In March, the company will reach a milestone of 1,000 births.

“We are social entrepreneurs,” Wyatt says. “We make money to spend it back in the community and try to disrupt the routine social and economic assumptions of what constitutes acceptable healthcare. We want women to seize the opportunity to change the aspects of healthcare that need to be changed.”

And as someone who has carved a unique path to success, she adds that her academic route through the College of Engineering was an excellent start because it exposed her to many different ideas and experiences.

“I would tell today’s engineering students to seize as many opportunities to learn different things as they can,” Wyatt says, “because you never know where you’re heading or how you’ll get there, and you need to take that intellectual energy and apply it to whatever you end up doing.

“And to the College of Engineering, I would add, ‘please keep rooting for the crazy ones.’”